How The Very Hungry Caterpillar Became a Classic

Eric Carle’s colorful story about metamorphosis remains a staple of baby showers and classroom bookshelves 50 years after its release.

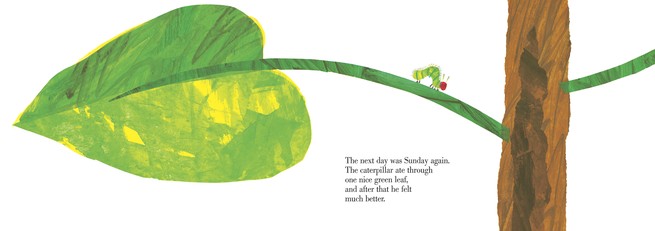

It happens pretty much the same way every time. The day after I’ve partaken in some sort of weekend or holiday eating-and-drinking binge—i.e., the Monday after the Super Bowl, the fifth of July, the first week of January after the entire Thanksgiving-through-New Year’s season officially comes to a close—I engage in the same detoxifying, repenting ritual: the consumption of a fresh, nutrient-rich salad. Somehow, in my mind, the more vividly green the leaves in the salad, the more purifying the ritual will feel, and with that first crunch on a crisp piece of greenery, I hear a tiny voice in my head, murmuring, “The next day was Sunday again. The caterpillar ate through one nice green leaf, and after that he felt much better.” A pivotal line from a formative piece of literature that I, like many thousands of other now-adults, first encountered in childhood: The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar—in which a caterpillar hatches out of an egg on a Sunday, proceeds to eat vibrantly colored fruits it finds in escalating quantities from Monday to Friday, goes on a junk-food-eating rampage on Saturday, eats a nice green leaf on Sunday, and then nestles into a cocoon for two weeks and emerges a beautiful butterfly—was released 50 years ago, on March 20, 1969. In the years since, it has sold almost 50 million copies around the world, in more than 62 languages; today, according to the book’s publisher, Penguin Random House, a copy of The Very Hungry Caterpillar is sold somewhere in the world every 30 seconds. And its enduring appeal, according to librarians and children’s-literature experts, can be attributed to its effortless fusion of story and educational concepts, its striking visual style, and the timelessness of both its aesthetic and its content.

Michelle Martin is the Beverly Cleary Professor for Children and Youth Services at the University of Washington’s Information School—meaning that every day, she trains future teachers and school librarians in how to teach reading and literacy. She also publishes reviews of children’s books. In Martin’s field, if you don’t have a good grasp of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, “you are children’s-book illiterate,” she says with a laugh.

Part of why both kids and parents love The Very Hungry Caterpillar is because it’s an educational book that doesn’t feel like a capital-E Educational book. Traditionally, children’s literature is a didactic genre: “It teaches something,” Martin says, “but the best children’s books teach without kids knowing that they’re learning something.” In The Very Hungry Caterpillar, she adds, “you learn the days of the week. You learn colors. You learn the fruits. You learn junk-food names. In the end, you learn a little bit about nutrition, too: If you eat a whole bunch of junk food, you’re not going to feel that great.” Yet, crucially, none of the valuable information being presented ever feels “in your face,” Martin says.

Kim Reynolds, a professor of children’s literature at Newcastle University in England, notes that Caterpillar’s lessons about nutrition are especially valuable for kids. “The fact that the process indulges not just hunger but the joys of food—taste, texture, colors, scents are all evoked by the range of food the caterpillar eats—intensifies the delights,” she writes in an email. The book also presents opportunities for kids to feel playfully superior to the caterpillar when it overindulges and gets a tummy ache. (Perhaps only later in life do readers learn to feel sorrowful, indigestive empathy for the gluttonous caterpillar.)

But The Very Hungry Caterpillar doesn’t just stop at the colors, numbers, healthy eating, and days of the week, Martin points out: It also offers a nifty lesson in elementary animal biology. “You do get a little bit of a lesson as the caterpillar goes into the cocoon and then comes out as a butterfly,” Martin says, and adds with a laugh, “How many 2-year-olds are conversant about metamorphosis?” Certainly more than might be otherwise, thanks to The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Reynolds believes that the narrative about transformation can also be understood as an age-appropriate allegory about growing up. “At some level the story is recapitulating the journey from childhood to adult[hood] and presenting it as an entirely positive transformation,” she said. “You start off small and hungry (for healthy babies, food is the first source of bliss and connection with the carer), and you grow up to become gorgeous.” (This is Carle’s understanding of the story, too: “Like the caterpillar, children will grow up and spread their wings,” he has said of the book.)

Another aspect of The Very Hungry Caterpillar that has added to its perpetual popularity is its vivid, subtly sophisticated art. “The art in that book is just fantastic,” Martin says, and unusual elements such as holes in the pages where the caterpillar has eaten through a food make it a particularly memorable reading experience for small children. Plus, as Martin points out, much of the art in Caterpillar and the rest of Eric Carle’s oeuvre—including in works such as The Very Busy Spider and Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?—uses bright colors and formal techniques that are familiar to small children, such as finger painting and overlapping paper cutouts. “Kids think, ‘Oh, I could do that!’” Martin says. The sun in The Very Hungry Caterpillar, she points out, even has a smiley face.

That said, the childlike themes in Carle’s illustrations belie the complexity and invention of his visual style—something that was unusual in children’s books when Caterpillar was first published in 1969. “I do think it’s intentional on Carle’s part to make the art look like that, because it draws the child in,” Martin says, but she adds that creating the imagery for Carle’s children’s books was in fact an intricate and complicated process, and Carle was also producing art that showed in galleries at the time. “It used to be that illustration was kind of a second-class thing, if you were an artist,” Martin says. In that way, Carle was ahead of his time. “There weren’t nearly as many dedicated career illustrators in the 1960s as now. Today [illustrators] will push the boundaries more, and create art that’s gallery-worthy, but it’s for a picture book.” Carle, she adds, has his own gallery in Massachusetts—the Eric Carle Museum in Amherst, which is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the book with its own special exhibition.

In some ways, The Very Hungry Caterpillar is typical of its time. In the late 1960s, “there was quite a lot of psychological training for teachers about everything from children’s fears to color perception; there was much encouragement for young children to explore the world (safely),” Reynolds said. “Bright colors, everyday objects, uncluttered design, and a joyful, optimistic approach to life” were in vogue in children’s literature at the time, and they’re also splashed all over the pages of The Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Still, while many children’s books of the era engaged with the real world and with nature, Martin says, few did so as whimsically as The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Especially in the United States, she points out, much of the children’s literature of the 1960s had a distinctly Civil Rights–era, activist bent to it. (Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day, the first book about an African American child to win the Randolph Caldecott Medal, was published in 1963.) Plenty of classic children’s books from 1969, in other words, immediately announce their from-1969-ness in a way that Martin thinks The Very Hungry Caterpillar does not.

“The Very Hungry Caterpillar has aged very well. There’s nothing in there to tie it to 1969, really,” she says.

For that reason, Martin says she fully expects The Very Hungry Caterpillar to still be a wildly popular baby gift and classroom staple another 50 years from now. “All those things are still around, that the caterpillar encounters,” she says. “And kids are always going to need to learn the days of the week.”