Want more inspiring, positive news? Sign up for The Good Stuff, a newsletter for the good in life. It will brighten your inbox every Saturday morning.

When Aimee Ingabire stepped off the plane with her mother, taking her first steps on American soil after a 32-hour journey from the Republic of Congo, she knew her life had changed forever.

There she was in Seattle, a 15-year-old fleeing war, thousands of miles from her homeland and suddenly disconnected from her culture and the only language she knew.

Ingabire is one of dozens of refugees whose stories have been turned into art by Karisa Keasey, a painter and storyteller.

Six years ago Keasey became aware of the global refugee crisis when learning about the civil war in Syria. Inspired to change the way people viewed immigrants and refugees, the 30-year-old wrote a book based on the stories of refugee survivors who were able to reach the United States.

Her book, “When You Can’t Go Home,” consists of 10 stories of refugee families who have resettled in the Pacific Northwest following years of hardship.

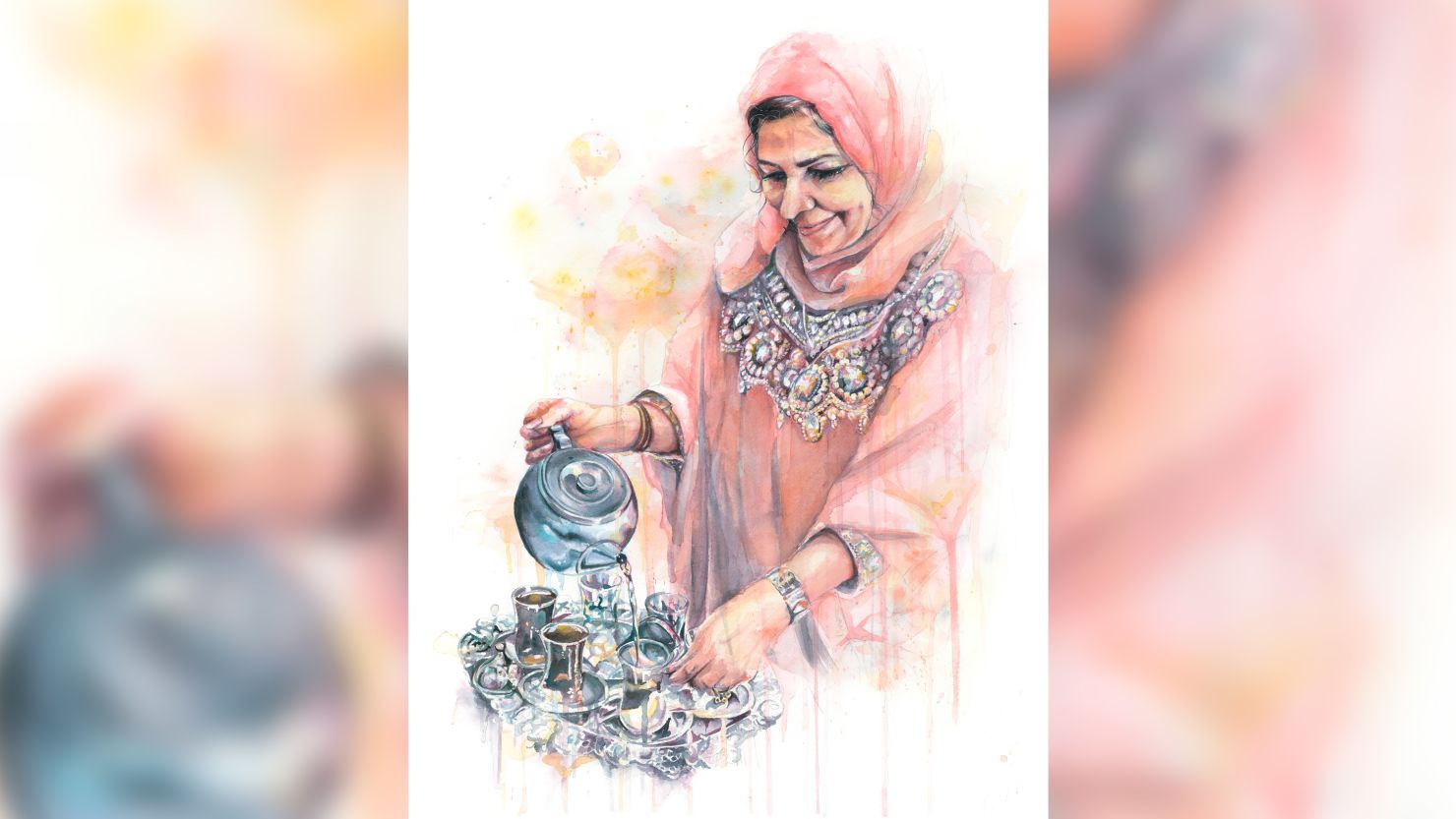

“There is a disconnect between who refugees are and how they are often portrayed in the media,” Keasey told CNN. “They are not terrorists, victims or saints. They are people. I painted images of what I saw: mothers, fathers, siblings, entrepreneurs, artists, doctors and grandparents who are more than their status as a refugee. I painted their humanity.”

The heart-wrenching stories feature people from various backgrounds. There is Taghreed, a woman who left Iraq because of the war, for example, and Ahmad, who was nearly killed by the Taliban. Thirty stunning watercolor portraits, carefully painted by Keasey, accompany their stories.

They touch on various scenarios common among refugees, ranging from the conflicts they face in their home countries, life in refugee camps and detention centers and the process of attaining refugee or asylee status.

While her goal is to raises awareness about the refugee crisis and “spread empathy and respect” for the experiences they face, Keasey is also donating 50% of the book’s profits to the refugee resettlement organization World Relief.

A glimpse into the life of a refugee

Ingabire was born in a refugee camp in the Republic of Congo, after her family fled Rwanda to escape genocide. Despite embracing Congolese culture as their own, as refugees Ingabire and her family often felt unwelcome.

“Growing up as a refugee in Congo was a daily hardship. My parents struggled to provide basic necessities for my four brothers and I. The stress of living as refugees eventually tore my family apart,” Ingabire said.

“My parents divorced in 2005, when I was only 7 years old,” she said. “My mother could barely support her five young children, but she passionately believed in the power of education. She scraped together enough money to send me to middle school.”

After applying for refugee status through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Ingabire’s family was resettled in Kent, Washington, when she was entering high school and did not speak a word of English.

“As a refugee you feel like being born again because you feel like you have to relearn a lot of things, especially in a different language,” Ingabire said. “I think people fail to understand that many refugees wish to go to their home and be with their family but because of the war they are forced to seek help from other countries.”

Despite her excitement at her family’s opportunity to start a new life, Ingabire recalls feeling overwhelmed trying to navigate her new culture and language. Even lunchtime at school was terrifying, she says.

Now 22-years-old and a student at Northwest University majoring in psychology, Ingabire says she is thankful for Keasey’s dedication to refugees and the challenges they go through.

“The project truly portrays the life of refugees,” she said. “It was stories told by refugees themselves. People will be impacted by this, by knowing this is not a fiction story.”

“Not only will people read about our struggles,” she said, “but they will also understand that refugees have goals and we work hard to achieve them just like everyone one else.”